Speaking of AWP and Portland...I know you remember Portlandia’s “put a bird on it” episode. Every year there seems to be a new version of putting birds on things. There was the owl year. And hedgehogs.

Last year it was llamas and sloths, the latter slowly…in slothlike fashion...leading us out of the what-fresh-hell of 2018 and into 2019.

Sloth everything, including the microwavable hot pad my daughter gave to me after my concussion, and dog toys…

…which I guess sloths like too, apparently.

Now Virginia Woolf and To the Lighthouse seem to be the bird-on-it of the moment…

Maybe that’s wishful thinking on my part. It doesn’t take long to figure out that Virginia Woolf is one of my muses (the other being Lyra, who looks a bit like Virginia, don’t you think?)

As many of you know, Woolf’s theory of “moments of being”—those breathtaking experiences of complete awareness, the sense of being fully present and connected at once to yourself, the moment you’re living, and the world—and their relationship to the making of art is a foundational principle in my work with writers, as well as my own writing.

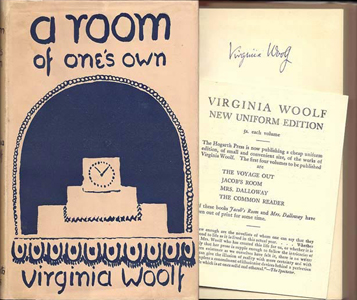

If I were in charge every contemporary woman writer would be required to read A Room of One’s Own, still head-shakingly relevant in its analysis of literary gender politics. (Wow, in the 1920s men rarely chose to read books by women! That’s so fascinatingly quaint, since a hundred years later…men rarely choose to read books written by women.)

Reading To the Lighthouse is a given not just for its stylistic audacity and beauty, its usefulness to other writers as a kind of working handbook of technical craft, but also as a prime example of artistic success propelled by the engine of the author’s emotion, of Woolf’s deep and wounded heart.

Her Writer’s Diary is invaluable for other writers, giving us a glimpse of Woolf’s mind at work as she faces down the possibilities and decisions, influences and anxieties attendant on her own writing process. So relevant still is A Writer’s Diary that The New Yorker recently republished W. H. Auden’s acute 1954 essay on the book’s release. “In her diary,” goes the NYer’s subhead, “Virginia Woolf left behind the most truthful record of what a writer’s life is actually like.”

There are a bunch of current VW articles floating around right now, too, perhaps in part because of the popularity of the facebook group What Would Virginia Woolf Do? and its subsequent spinoff website The Woolfer, both inspired by Nina Lorez Collins’ book on feminism and aging with grace, humor, and a sisterhood.

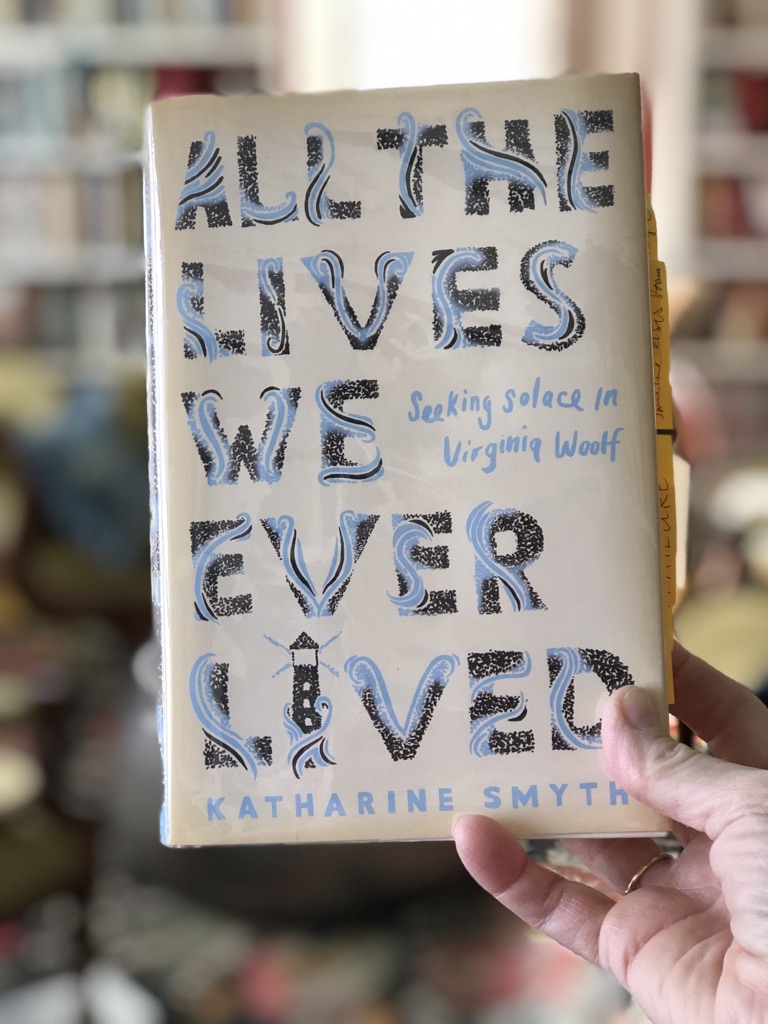

Into this Woolf zeitgeist arrives Katharine Smyth with her first book, the memoir All the Lives We Ever Lived: Seeking Solace in Virginia Woolf. Smyth’s antidote to the death of her favorite person, her father, is to reread To the Lighthouse, her favorite book—which she first read in her dad’s company, sitting in a wintry English parlor as her father listened to Handel.

“Perhaps there is one book for every life,” Smyth writes, a book that so synthesizes our own experiences and questions and desires that it seems to have anticipated us, knowing what we need even when we don’t know ourselves.

Katharine Smyth graciously agreed to tell us about the evolution of All the Lives We Ever Lived for our monthly series of Q&As with women writers, one of the exclusive features of our year-long mentorship and book cultivation program, Bookgardan. Before and during the interview Katharine and I had talked about how painful writing a memoir can be, and how strange it is that you are rarely warned about that possibility. I was thus surprised and moved by Katharine’s response to my question about the pain she must have felt in writing about her father after his death:

“A lot of people said, it must be so hard to write about your father, it must be so painful. But the truth is, I loved it. And I felt like it was really a way, almost every day, a way to go back to him and see him, it’s almost like . . . you can’t succeed in resurrecting someone, but it’s almost like having a standing appointment for grief, to be writing about them. That’s going to be the hardest part going forward, and it’s already been difficult. I’m not even thinking about my dad much anymore. I notice I dream about him a lot less than I used to, for instance. It was really nice to have a reason that I had to think of him every day, that I had to engage with his character every day. “

What strikes me doubly about Katharine Smyth’s emotional response to writing about her dad and his death in her memoir are the parallels and resonances to Woolf’s experience of her mother before and after writing To the Lighthouse. From the time of her mother’s death, Woolf wrote in her Writer’s Diary, she was obsessed with her mother, hearing her voice in her head almost daily for thirty years. By contrast, Woolf realized that she could hardly remember a single time spent alone in her mother’s company, so completely consumed was Julia Stephen in her role as the all-helpful Victorian “Angel in the House.” Woolf, like Smyth, must have found great satisfaction in the time she spent writing about her fictionalized mother, Mrs. Ramsay, about whom Woolf’s sister, Vanessa Bell, would say in a letter,

“ . . . You have given a portrait of mother which is more like her to me than anything I could ever have conceived of as possible. It is almost painful to have her so raised from the dead. You have made one feel the extraordinary beauty of her character, which must be the most difficult thing in the world to do. It was like meeting her again with oneself grown up & on equal terms & it seems to me the most astonishing feat of creation to have been able to see her in such a way . . .”

Get another taste of Katharine Smyth’s memoir and Woolf’s impact on her in this piece at LitHub, “How Virginia Woolf Taught Me to Mourn,” and also in “Where Virginia Woolf Listened to the Waves” at The Paris Review.

And if your curiosity has been whetted for our year-long mentorship & book cultivation program, you can find more information here at Bookgardan.